New Frontiers in International Business and Economic Sustainability

Devan Jaques

402G Solutions Inc. Advisor

This article suggests that aligning project goals with sustainable initiatives not only generates returns for investors but also integrates transnational initiatives that contribute to broader global and environmental success.In contrast, restrictive or poorly designed policies can lead to significant geopolitical repercussions and exacerbate social challenges in economically disadvantaged nations. Such policies are unattractive to investors and can severely hinder foreign direct investment (FDI), deepening economic and societal disparities. Southeast Asia, which experienced a turbulent and tragic aftermath following decolonization in former French Indochina, is now transforming its trajectory. The region is demonstrating resilience and progress, moving towards a more promising and stable future.

Alignment of Global Standards: Regulatory Challenges and Opportunities

Social and environmental factors are playing an increasingly significant role in shaping investment decisions, becoming inseparable from economic progress and perceptions of sustainability. Frameworks like the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) play a big part in why investors and governments alike may prioritize ethical and eco-friendly projects. However, not all jurisdictions adhere uniformly to international standards, and some pose significant challenges for investors. Inconsistencies in legal frameworks, regulatory enforcement, and political instability can create significant barriers to attracting foreign investment. In the early 1990s, the Foreign Investment Advisory Service (FIAS), a collaboration between the World Bank and IFC, identified widespread challenges for both governments and foreign investors regarding obstacles to implementing private infrastructure projects (Sader, F., 2000). These difficulties were primarily caused by the lack of clear policy frameworks and the absence of institutional mechanisms to effectively address barriers or guide the allocation of large-scale investments (Alfaro et al., 2004). Without well-defined regulations and reliable enforcement, the investment climate becomes unpredictable, deterring potential foreign capital. Interestingly, many states which found themselves on the FIAS’ pejorative list remain in similar positions, while others have made material strides in a more favourable direction.

Lessons from more recent decades highlight the critical role of international standards, such as those established by the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL), the World Trade Organization (WTO), and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), in guiding investment flows and fostering sustainable economic growth. By adhering to frameworks like the WTO’s Trade-Related Investment Measures (TRIMs), OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, and bilateral investment treaties, nations attract foreign capital while bolstering economic resilience, reducing regulatory risks, and promoting inclusive development. These frameworks emphasize transparency, accountability, and fairness, establishing clear rules for taxation, corporate governance, and dispute resolution, while additionally ensuring respect for domestic legal sovereignty.

Although geopolitical disparities can complicate investment processes, exploring new commercial frontiers often fosters global cooperation through the alignment of shared objectives. Adherence to international trade agreements and frameworks mitigate power imbalances that may arise between large-scale investors and their host communities. Conversely, deviations therefrom create challenges in attracting investment capital.

Socioeconomic Consequences of Restrictive Policies

Regional and multilateral agreements designed to reduce barriers simply cannot operate notwithstanding problematic domestic laws or policies (Ghosh et al., 2012; Gulen & Ion, 2015). Therefore, to effectively attract FDI, countries must optimize their regulatory frameworks to balance investor protection, market competition, and consumer welfare. However, FDI inflows also depend on broader factors such as macroeconomic stability, competitive policies, and an effective legal framework (Alfaro et al., 2004; Li & Liu, 2005).

A positive correlation between foreign direct investment (FDI) and economic growth is well-documented (Iamsiraroj & Doucouliagos, 2015). Restrictive policies can significantly hinder FDI, precluding economic growth (Zongo, F. 2021), whereas a competitive investment climate fosters job creation and sustainability (World Bank, 2005). FDI is known to enhance productivity, shift comparative advantages, reduce unemployment, and foster technological innovation (Hale & Xu, 2016; Dritsaki & Stiakakis, 2014). Studies also indicate that the relationship between FDI and growth is stronger in open economies with developed financial markets (Bodman & Le, 2013). Empirical evidence further suggests that foreign investment in manufacturing industries can positively impact individual caloric and protein intake, highlighting the central role access foreign investment can have in improving living standards (Mihalache-O’Keef & Li, 2011).

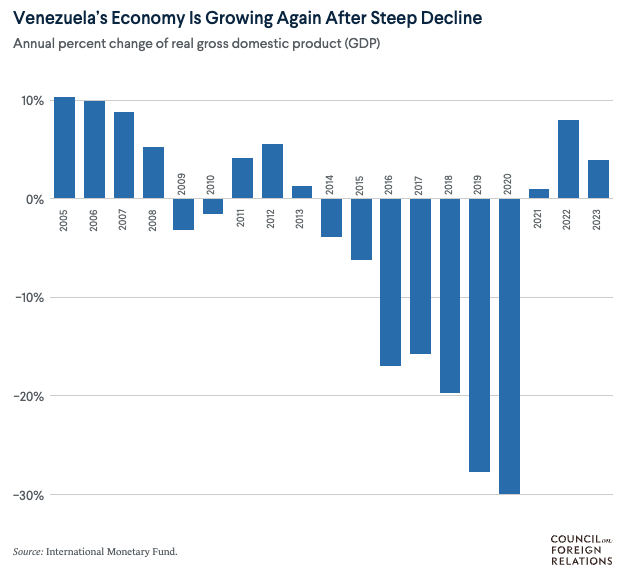

Regulatory frameworks that provide confidence in economic and political landscapes lower transaction costs and minimize investment risk- factors that are critical in attracting FDI. In South America, for example, Venezuela has faced intense scrutiny due to its volatile political climate, strict capital controls, and frequent shifts in investment policies. These factors have heightened risks for investors, leading to a significant decline in foreign capital. Policies introduced during the Chávez administration, including the nationalization of key industries and restrictive foreign investment regulations, drove away many foreign firms and debilitated the oil sector—historically Venezuela’s economic backbone. This erosion of productivity and infrastructure investment resulted in one of the most severe and prolonged GDP contractions in modern history (Alvarez et al. 2022). Nevertheless, Venezuela’s abundant natural resources, especially its vast oil reserves, present opportunities for recovery. Policy reforms focused on transparency, stable regulations, and the responsible use of resources could attract foreign expertise and investments, revitalizing the economy and fostering long-term growth.

Geopolitical risk influences the strategic interactions among international bodies based on their geographical location, resource endowment, economic structure, military power and other elements, such as cooperation (Hu, Shan et al. 2023). Unpredictable, unwritten, or otherwise ad hoc enforcement of policies, slow approval of investments and strict rules on repatriation of profits will, consequently, undermine foreign interest. In Africa, the regulatory framework that has caused much uncertainty is Zimbabwe, which is endowed with some of the most valuable mineral resources in the world. However, its use of forceful policies, such as the seizure of foreign properties, has created significant challenges (Tsaurai & Odhiambo, 2011). These legal measures, such as the real and intangible property indigenization policy, which requires foreign investors to cede majority shares to locals, have deterred foreign investment and have instead raised the risk of Zimbabwean dollars becoming almost worthless. These policies, combined with the country’s economic instability and hyperinflation, have greatly hindered the ability to attract and maintain foreign direct investment. According to Gwenhamo (2009), such standard deviations from global investment practices, fiscal deficits, and weak institutions, have dampened the economic development and the fiscal dividends of being a resource rich country such as Zimbabwe.

Progressing a Global Policy Agenda

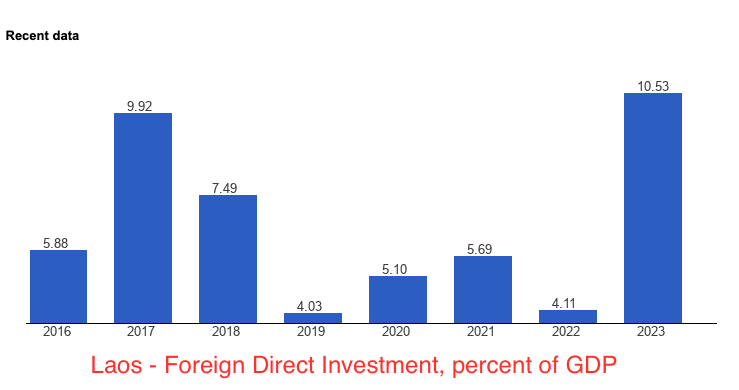

In Southeast Asia, FDI has greatly increased in places such as Cambodia and Vietnam, while others have significantly amended laws to transform their investment markets. Lao PDR, traditionally considered landlocked, is rapidly advancing its ambition to become “land linked,” by connecting to the broader Asian continent and moving towards international integration (World Bank, 2020; Tamin, 2024). Efforts to integrate the Lao economy within international markets are not new. Following the launch of an ambitious structural reform process in 1986 under the New Economic Mechanism, Lao PDR has since transitioned from a centrally planned economy to a more open, private sector-led, and market-oriented system. These reforms continue to progress the state from regime-oriented to market-oriented.

This creditable progress is now occurring by virtue of participation in international organizations and agreements. Following extensive negotiations, Lao PDR’s membership in the WTO was ratified in 2013 joining the ranks of regional counterparts Cambodia (2004), and Vietnam (2007). Accelerating further, in 2015, Lao PDR made itself one of the first countries worldwide to have ratified the Agreement on Trade Facilitation. This Agreement aims to expedite the movement, release, and clearance of goods, as well as enhance domestic capacity for international participation. The Lao PDR has shown clear commitment to modernizing its economy and aligning national plans with global priorities. In the pursuit of achieving the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030, the country has identified three priority investment areas that are believed to drive broader development and progress: universal access to modern energy, increased use of renewable energy, and improved energy efficiency. The effect of this ambition will likely entrench the participation of foreign markets within the country, consequently coalescing the Laotian economy with the more substantial economies of its regional and continental neighbors.

Lao PDR has actively positioned eco-friendly hydropower development as central to its overall development agenda. This strategy seeks to ‘develop new renewable energy resources which are not yet widely explored in Lao PDR’, and to ‘replace resources that will be exhausted in the future’ (Renewable Energy Development Strategy in Lao PDR, 2011). The aims of creating of renewable sources of energy appears to reconcile market competitiveness with environmental sustainability and ethics. Other energy sources- such as biomass, oil, gas, and petroleum- which presently comprise the majority of Lao energy consumption, are expected to be replaced by electricity exports. Now, these exports are expected to more than triple by 2030 (Phongsavath, 2024).

Accordingly, Lao PDR can more effectively participate in international value chains simply by letting location-driven market forces take place (World Bank Group, 2021). As the Lao government continues to rely on the electricity sector as a major driver of growth, this will now be reinforced as a source of increased revenue through exports to regional trade partners. As the trajectory was already ‘up’, localized supply chains will only assist this positive trend. For example, the electricity sector nearly tripled its share of the economy over the past decade, accounting for 21% of exports in 2021 and 25% in 2022/3; substantial increases compared to 5% in 2010 (Bank of Lao Economic Report, 2021).

New Frontiers in Foreign Investment

The historical background of Southeast Asia, particularly the Indochina colonial experience, has played a significant role in shaping the region’s modern infrastructure. From the French colonial era to only recently, infrastructure development has been closely tied to resource extraction, leaving many local nations, including Laos, with infrastructure networks focused largely on consolidating control over non-renewable resources (Burlette, 2007). Even after the end of their respective colonial periods, the infrastructure of countries like Laos continued to suffer from fragmentation, largely due to the widespread destruction caused by the wars across Indochina, most notably the Vietnam War. Between 1955 and 1975, most of Laos was heavily bombed by the United States, leaving most of the infrastructure ruined, unfit for agriculture, as well as with significant residual casualties and hazards (World Bank, 2023). The Lao PDR government has sought to rebuild infrastructure, which is still underdeveloped today (Hennings, 2024), however, the modern benchmark appears to be financial and eco-sustainability.

Large developmental gaps and unique geography make infrastructure development in Southeast Asia particularly important for economic growth and regional cohesion. However, recent years have yielded substantial infrastructure investment in Southeast Asia, driven by projects such as China’s Belt Road Initiative. Pursuant to this initiative, Lao PDR has taken important steps towards modernization- including flagship infrastructure projects, such as the newly completed Lao-China Railway. This railway line between Vientiane and Kunming offers a new economic perspective for the region. Such projects are improving regional connectivity and economic integration between Lao PDR and more advanced economies. But the project has also brought a sharp rise in Lao public debt, estimated at $5.9 billion, raising concerns over financial dependency on China (World Bank, 2020). It will, however, potentially better place Laos to play a more central role in the regional economy, and it is conceivable that Laos’s emergence in the regional economic landscape might ultimately be attributed to the railway project. Pursuant to the UN SDGs, achieving on-ground connectedness may finance more ambitious projects within the region and mitigate dependence on external state actors.

To meet the WTO standards, Lao PDR promulgated a multiplicity of new laws and regulations on trading rights, import licensing, customs valuation, investment policies, technical barriers to trade, and protection of intellectual property. The Ministry of Planning and Investment oversees responsibilities such as formulating and implementing policies at the macro level. It ranges from promotion and regulation of foreign and domestic investment, promotion, and regulation of development and operation of Special Economic Zones (SEZs) in Lao PDR.

Lao PDR’s domestic progress presents promising opportunities, but achieving sustainable returns on investment requires navigating a complex regulatory landscape. Investors must comply with local laws amid opaque international jurisdictions, facing challenges such as inconsistent legal frameworks, overlapping regulations, and jurisdictional conflicts. Additional hurdles include understanding tax and trade laws, safeguarding intellectual property, and adhering to labor and environmental standards. Cultural differences, language barriers, and limited access to reliable legal expertise further complicate matters. Overcoming these obstacles demands a thoughtful approach to risk mitigation, to ensure compliance, and to build productive international partnerships.

Conclusions

Aligning sustainable project goals with transnational initiatives, such as the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, not only generates returns for investors but also promotes global and environmental success. Conversely, restrictive or poorly designed policies can lead to significant geopolitical consequences and exacerbate social challenges in economically disadvantaged nations. Problematic regulatory frameworks are unattractive to investors and can hinder FDI, worsening economic and societal disparities. Numerous studies suggests that enhancements to manufacturing, technology and job creation, leads to direct societal benefits including the overall level nourishment its citizens receive (Mihalache-O’Keef & Li, 2011). Private sector investment, therefore, can yield exceptional benefits in assisting a nation’s economic and social growth.

In this way, private sector investments directly enhance living conditions, drive macroeconomic growth, and assists with public sector efforts to achieve eco-stability and sustainability. Southeast Asia, once marked by the turbulent aftermath of decolonization in former French Indochina, is now demonstrating economic opportunity for FDI while exhibiting strong commitments to environmental sustainability. The region is shifting toward a more promising private sector investment climate, and consequently, a more stable future of lasting growth and development.

Given a global multiplicity of geopolitical realties, successfully navigating foreign investments in large-scale projects requires a strategic approach, especially when entering previously unexplored frontiers. Companies must negotiate tax concessions effectively to ensure financial viability and maximize returns. Establishing a clear and mutually beneficial Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs) is essential for aligning objectives and strengthening partnerships. 402G Solutions Inc., by virtue of their business processes and protocols, have developed strategies for navigating these challenges.

Setting up robust organizational and operational structures is crucial for ensuring seamless execution. However, disparities and inconsistencies in regulatory markets also underscore the importance of conducting thorough risk assessments and tailoring strategies to the specificities of diverse jurisdictions. To achieve global favourability, and to inspire investors alike, a comprehensive investment recovery plan is vital for long-term profitability, enabling the project to generate broader benefits for the host nation, including job creation, tax revenue, infrastructure development, and sustained economic growth. By achieving these interconnected goals, a company can position itself as a key driver of enduring progress and shared prosperity.

Works Cited and Consulted

Alfaro, L., Chanda, A., Kalemli-Ozcan, S., & Sayek, S. (2010). Does foreign direct investment promote growth? Exploring the role of financial markets on linkages. Journal of Development Economics, 91(2), 242-256.

Alvarez, J. A., Arena, M., Brousseau, A., Faruqee, H., Fernandez Corugedo, E. W., Guajardo, J., Peraza, G., & Yepez, J. (2022). Regional spillovers from the Venezuelan crisis: Migration flows and their impact on Latin America and the Caribbean. Departmental Papers, 2022.

Bank of the Lao Democratic People’s Republic (BOL) (2021), Annual Economic Report 2020, Vientiane.

Burlette, J. A. G. (2007). French influence overseas: The rise and fall of colonial Indochina (Master’s thesis). Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College.

Dritsaki, C., & Stiakakis, E. (2014). Foreign direct investments, exports, and economic growth in Croatia: A time series analysis. Procedia Economics and Finance, 14, 242-247.

Gwenhamo, F. (2009). Foreign direct investment in Zimbabwe: The role of institutional factors. Journal of Development Studies, 45(6), 985-999.

Hennings, A. (2024). Laos – Context and land governance. Land Portal.org.

Hu, W., Shan, Y., Deng, Y., Fu, N., Duan, J., Jiang, H., & Zhang, J. (2023). Geopolitical risk evolution and obstacle factors of countries along the Belt and Road and its types classification. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 365.

Mihalache-O’Keef, A., & Li, Q. (2011). Modernization vs. dependency: Venezuela’s economic landscape.

Phongsavath, A. (2024). Renewable Electricity and Energy Transition in Lao PDR: Opportunities for Green Hydrogen and Ammonia’, (eds.), Energy Security White Paper: Policy Directions for Inclusive and Sustainable Development for Lao PDR and the Implications for ASEAN. Jakarta: ERIA, pp. 198-230.

Sader, F. (2000). Attracting foreign direct investment into infrastructure: Challenges and lessons from developing economies. World Bank Publications.

Tamin, R. (2024). From landlocked to landlinked: Transport connectivity development in Lao PDR. European Institute for Asian Studies.

Tsaurai, K., & Odhiambo, N. M. (2011). Foreign direct investment and economic growth in Zimbabwe. University of South Africa Research Papers.

World Bank. (2020). From landlocked to land-linked: Unlocking the potential of Lao-China rail connectivity. World Bank Publications.

World Bank. (2023). Resilient and Low Carbon Agriculture in Lao PDR: Priorities for a Green Transition. World Bank Publications.

Xiaoying Li, Xiaming Liu. (2005). Foreign Direct Investment and Economic Growth: An Increasingly Endogenous Relationship, World Development, Volume 33, Issue 3, Pages 393-407.

Zongo, F. (2021). The effects of restrictive measures on cross-border investment: Evidence from OECD and emerging countries. Journal of World Economics, 25(4), 340-352.